Explore 7 clinical scenarios to learn more about the management of atopic dermatitis.

Clinical Scenarios

-

You diagnose atopic dermatitis in a 4-month-old. The patient has erythematous patches on the face (Figure), extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees, and trunk. You discuss your diagnosis and principles of management with the family. How would you manage the erythematous patches?

Courtesy of Daniel Krowchuk, MD

Discussion

A low-potency topical corticosteroid (eg, hydrocortisone 1% or 2.5%), applied twice daily as needed, is indicated for the management of flares of atopic dermatitis in infants. It is also recommended for treatment of atopic dermatitis on the face in patients of any age. Ointment vehicles are preferred because they tend to be more effective, although some families prefer creams because they are less greasy. Once the erythematous patches resolve (usually within a few days to 2 weeks), the topical corticosteroid may be withdrawn and daily skin care measures continued.

-

You are evaluating an 8-month-old for worsening atopic dermatitis. The patient’s mother reports that the infant’s skin was clear until about 10 days ago when they experienced a flare involving the face, trunk, and extremities. There has been no improvement despite the application of hydrocortisone ointment 2.5% twice daily. The infant’s mother states that they usually respond rapidly to topical hydrocortisone. The physical examination results are normal except for the skin. There are erythematous patches on the face and extensor elbows and knees and areas of oozing and crusting (Figure). How would you manage this patient’s condition?

Courtesy of Daniel Krowchuk, MD

Discussion

The infant presented is experiencing a flare of atopic dermatitis (manifested by the appearance of erythematous patches on the face and extensor extremities) complicated by secondary infection with Staphylococcus aureus (as reflected by areas of oozing and crusting). Accordingly, in addition to continuing topical hydrocortisone and daily skin care measures, it would be appropriate to administer an oral antistaphylococcal antibiotic (eg, cephalexin or other agent based on local antibiotic resistance patterns) for 7 to 10 days. Some clinicians prefer to obtain a bacterial culture and sensitivity before initiating presumptive treatment, while others will do so only if the patient fails to improve within 48 hours. -

It’s summer and you are evaluating an 8-year-old for “light spots” on the face. The child’s mother reports that the spots first appeared about a month ago and have become more noticeable over time. She is concerned that her child may have vitiligo. The patient is in good health and has been using no medications or creams on the face. The patient’s past medical history is notable for “eczema” as an infant. The physical examination is normal except for the facial skin (Figure); there are no lesions elsewhere. Some of the lesions have overlying fine scale. What is your diagnosis and how would you treat the child?

Courtesy of Daniel Krowchuk, MD

Discussion

This child has pityriasis alba, a form of post-inflammatory hypopigmentation seen in children who have a history of atopic dermatitis. It appears as poorly defined hypopigmented macules that may have overlying fine scale. Lesions most often occur on the face and become more noticeable following sun exposure, when normal skin darkens but affected areas do not. Although the child’s mother is concerned about vitiligo, that is not the diagnosis. Unlike in vitiligo, the child’s lesions are not well defined (there is a gradual, not abrupt, transition from normal to abnormal color) and not depigmented (ie, the skin is not white).

Many clinicians believe that an emollient is sufficient treatment for most patients who have pityriasis alba. However, others prefer a brief course of a low-potency topical corticosteroid or topical calcineurin inhibitor to treat any remaining inflammation, especially if the areas are erythematous or pruritic. Families should be counseled that several months will be required for pigmentation to return to normal. Also, if new pruritic or erythematous areas appear, they should be treated with a topical anti-inflammatory agent in an attempt to prevent the development of hypopigmentation.

-

You evaluate an 11-year-old for eczema. The patient’s mother states that her child first developed eczema as an infant. In recent years, the patient has experienced occasional flares, especially in the flexures of the arms. However, a few weeks ago the patient developed rash and itching that has not responded to hydrocortisone 1% cream applied twice daily. The child’s examination is normal except for the antecubital fossae (Figure). How would you manage this patient’s condition?

Courtesy of Daniel Krowchuk, MD

Discussion

The patient has a flare of atopic dermatitis in the antecubital fossae and there is evidence of lichenification (thickening of the skin due to scratching). A clue to the presence of lichenification is the prominence of skin markings—as the skin becomes thicker the markings are relatively deeper and more apparent.

The patient has not responded to a low-potency topical corticosteroid. Most older children and adolescents will require a mid-potency preparation (eg, triamcinolone 0.1%, fluocinolone 0.025%) to control disease flares on the extremities. This is especially true if lichenification is present. Because the skin is thicker, absorption of the topical steroid is reduced. Ideally, you would select an ointment vehicle that offers occlusion and enhanced absorption of the corticosteroid. However, some patients do not like the greasy feel and will prefer a cream.

In addition to changing the topical corticosteroid, you would review with the mother and child the elements of daily skin care for those who have atopic dermatitis. This would include the importance of emollient application, especially during cold-weather months; avoiding triggers such as fragrances; and, to the extent possible, wearing cotton clothing next to the skin.

-

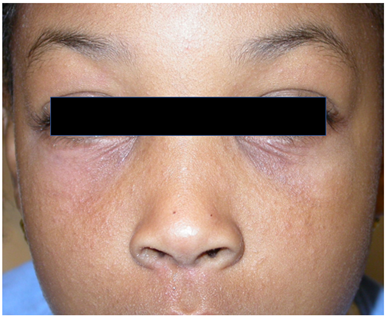

You evaluate a 9-year-old for atopic dermatitis. The child’s mother reports that her child has had eczema since infancy. Over the past several months, the patient has been experiencing flares on the face that have not responded well to the application of hydrocortisone ointment 2.5% twice daily. The child is using a fragrance-free moisturizer daily. The patient’s physical examination is unremarkable except for the face (Figure). How would you manage this patient’s atopic dermatitis?

Courtesy of Daniel Krowchuk, MD

Discussion

This patient has atopic dermatitis with prominent facial involvement. As is often the case in older children and adolescents, the periocular and perioral regions are involved. The patient’s skin tone makes erythema less apparent and, as in many patients with dark skin tone, many lesions are papules rather than patches.

The child is applying a low-potency topical corticosteroid (hydrocortisone ointment 2.5%) twice daily. This is an appropriate initial strategy for managing flares on the face, but, for this patient, it has been inadequate. Selecting a more potent agent would seem to make sense. However, because the skin of the face is thin it is not possible to increase potency without risking skin atrophy. One option is to use a non-corticosteroid topical calcineurin inhibitor (tacrolimus or pimecrolimus) either combined with hydrocortisone (one agent applied in the morning and the other at bedtime) or in place of hydrocortisone. Another option is to substitute a non-corticosteroid topical phosphodiesterase inhibitor (eg, crisaborole) for the hydrocortisone. -

You see a 5-year-old for follow-up of atopic dermatitis. The parents advise you that the child has been doing well and that the triamcinolone cream 0.025% that you prescribed has helped in treating disease flares. However, the patient complains of “stinging” when the cream is applied and has become hesitant to permit the parents to do so. How would you approach this problem?

Discussion

Stinging following the application of a topical corticosteroid is an uncommon but well-recognized occurrence. Most often, it is attributed to an irritant effect of preservatives contained in the vehicle, usually a cream. Usually, this can be remedied by substituting a topical corticosteroid ointment that is less likely to contain preservatives.

True allergic contact dermatitis due to components of a vehicle occurs rarely. It is characterized by persistent or worsening “atopic dermatitis” at sites of topical corticosteroid application. If allergic contact dermatitis is suspected, referral for patch testing is warranted. -

You evaluate a 6-year-old for eczema. The patient and family recently moved to the area and are new to your practice. The child’s mother reports that her child has had eczema since infancy and is concerned that flares have been increasing in frequency. During flares, itching is severe and has not responded to the application of hydrocortisone cream 2.5%. The family is not applying a moisturizer and is not using a fragrance-free cleanser. The patient’s physical examination is normal aside from the skin. The child has large erythematous patches involving the antecubital and popliteal fossae and smaller patches scattered elsewhere on the arms and legs. How might you manage this patient’s condition?

Discussion

There are several opportunities to enhance this patient’s skin care. You might review these with the family and advise them that the new plan likely will help heal the current flare and reduce the frequency of new ones. Your recommendations could include

- Daily preventive measures, including applying a fragrance-free emollient, using a fragrance-free non-soap cleanser, using an additive-free detergent and fabric softener, and wearing soft cotton clothing next to the skin when possible.

- Because the use of hydrocortisone cream 2.5% has been ineffective, you could prescribe a mid-potency topical corticosteroid (eg, triamcinolone 0.1%, fluocinolone 0.025%) applied twice daily during flares on the extremities. Several days to 2 weeks of treatment may be needed to control the flare.

- To prevent recurrent flares, once control is achieved, consider a single twice-weekly application of the topical corticosteroid to the most problematic areas.

- During flares you might consider recommending a bedtime dose of a sedating H1 antihistamine, such as hydroxyzine or diphenhydramine, to help the child fall asleep.

Having moderate or severe atopic dermatitis may have a negative effect on quality of life. Of course, optimizing treatment may mitigate this effect, but it may be helpful to explore some areas with the family.

- Are there sleep disturbances? These are common in children with atopic dermatitis, especially during disease flares. Disrupted sleep may lead to irritability, difficulty concentrating, and poor school performance.

- Has the child had difficulties interacting with peers? Children with atopic dermatitis may be embarrassed by their skin lesions. This may negatively affect friendships and participation in group activities. Some children with severe disease are at risk for anxiety and depression.

- Do the parents perceive adverse effects of their child’s atopic dermatitis on family functioning? Parents may experience sleep disturbances or challenges posed by the time necessary to administer treatment. Some have concerns about their own mental well-being and the ability to function at work.

The development of this information was made possible through support from Sanofi and Regeneron.