Reframing the Conversation about Child and Adolescent Vaccinations: Full Report

Download the full PDF version of the Framework Report to see in detail the strategies used to arrive at the recommendations in this brief.

The public discourse about vaccination is at a crucial inflection point, and pediatricians and advocates have an important role to play in shaping that discourse. We need to shift toward a new narrative about vaccinations, one that can change the way people think and talk about the issue.

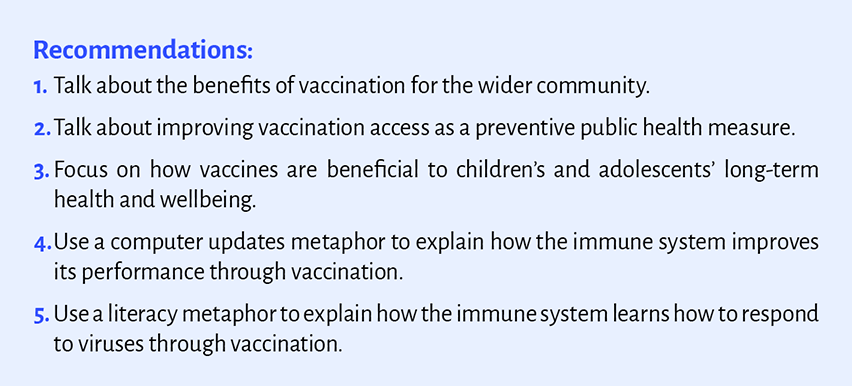

To that end, the AAP partnered with the FrameWorks Institute to conduct rigorous framing research that focuses on communicating about vaccines. Five evidence-based recommendations were developed, designed to equip physicians, advocates and public health communicators with the strategies they need to effectively build understanding of and support for child and adolescent vaccinations.

Since the first round of research, FrameWorks conducted additional qualitative research with rural residents. Recommendations here are revised with updated findings.

The framing recommendations are designed to be used flexibly and can be adapted for different audiences, speakers and messages. Pediatricians and communicators can advance a new story about vaccinations—one that is grounded in the latest vaccine science and the evidence on communicating about vaccines, so that we can build support for policies that increase access to vaccination for all children and adolescents.

Note, this research was created to support advocates who communicate about vaccines in the public square, where the goals include a creating broad cultural shift in the public’s understanding of vaccines. When it comes to counseling individual families during a health care visit, pediatricians and other clinicians should draw on existing evidence-based strategies.

Download the full PDF version of the Framework Report to see in detail the strategies used to arrive at the recommendations in this brief.

Get strategies to use talking points, sample letters to the editor, and social media messaging.

People think about health in highly individualistic ways. To make the case for a public response, we need to talk in terms of public health.

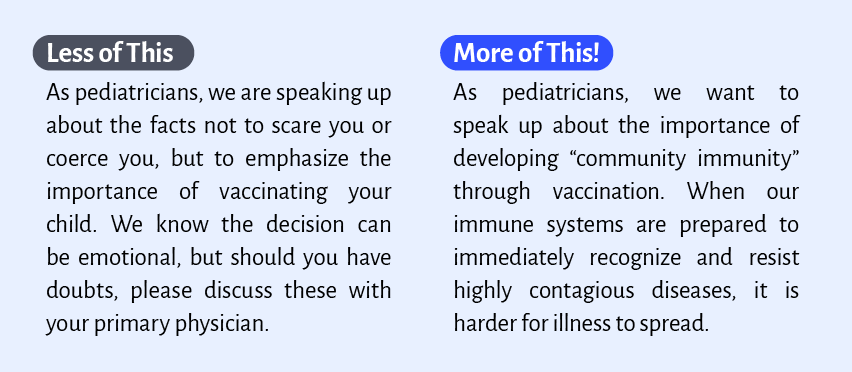

Emphasize collective benefits and responsibilities, but don’t violate individual autonomy.

Order matters. Lead with the community benefits of childhood vaccination, then connect those shared benefits to individual children, rather than the other way around.

Highlight what’s in it for the community. Be explicit about the benefits of childhood vaccination to communities such as the benefits of healthy settings for school and extracurricular activities.

Foreground collective responsibilities. Talk about our shared obligation to keep everyone, including children, healthy - and connect that to immunization. This is a community-wide effort!

People don’t see the practical barriers to getting kids vaccinated. Talk more about the importance of access to vaccination.

People think about vaccines in terms of risk-reward. Right now, the “rewards” are intangible for the public.

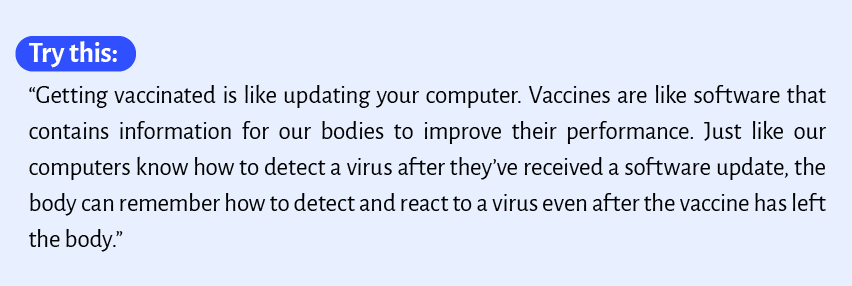

When we rely on military language, people conclude that any transmission of disease indicates a failure of the vaccine. When we compare childhood vaccines to medicine, we heighten people’s concerns about side effects. When we compare vaccinations to computer updates, we call up productive associations like prevention, ongoing maintenance and protection against “network” threats.

When we compare gaining immunity to gaining literacy, we tap into beliefs that the ability to read benefits both individuals and society, and that it’s best to gain literacy in childhood.

These recommendations were designed to carry out a much-needed 2-pronged narrative shift.

Shifting the focus from the individual to the collective: The American public’s understanding of health is grounded in individualistic ideas about what health entails and who’s responsible. People think that health is a matter of individual choice and willpower, rather than thinking about the broader communitywide or society-wide impacts that affect health. When thinking about vaccination, this individualistic approach gets in the way of understanding the broader benefits that vaccination, and particularly childhood and adolescent vaccination, have on communities and society. It also makes it difficult for people to see how systemic barriers to vaccination access affect people’s ability to get their children vaccinated, rather than vaccination simply being about individual choice. Instead, we need to highlight the ways vaccination has a positive impact on society and that improving vaccine access is an issue that affects everyone.

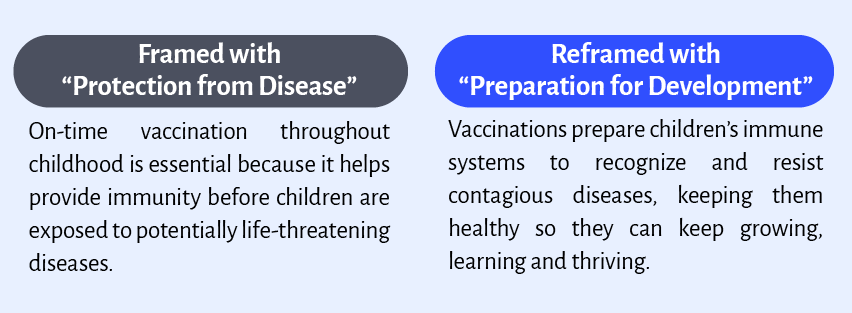

Shifting the focus from vaccines fighting disease to the immune system preparing itself: Currently, public thinking about vaccines tends to overemphasize the risks involved. This is because people focus on what vaccines do to the body, which makes them suspicious about the potential harms involved. The widespread misinformation about vaccinations, particularly for measles and COVID-19, stoke this fear about what vaccines might “do” to an individual. Instead, we need to highlight what the immune system does—how it uses vaccines to prepare itself to deal with illness and disease, which will help expand people’s understanding of how vaccines work and reduce fear surrounding vaccination.

Recommendations 1, 2 and 3 have been designed specifically to help shift the focus from the individual to the collective, by tapping into widely shared values and talking about what’s at stake in the issue.

Recommendations 4 and 5 are metaphors that have been designed to shift the focus from talking about vaccines fighting a disease, which leads to people overemphasizing risk, to explaining how the immune system prepares the body for the virus. These metaphors expand people’s understanding of vaccines as “trainers” that help the body prepare itself to become proficient in fighting illness, reducing fear about what vaccines might do to the body.

With more effective, evidence-based framing, we can move the public discourse on vaccines from contentious and emotional to productive and inspiring, and in this way build support for necessary policy change to improve access to vaccination for children and adolescents.

11/13/2024

American Academy of Pediatrics