Kelly M, Davis K, Stephens-Shields A, Rand C, Steffes J, Localio R, Macario E, Albertin C, Humiston S, Grundmeier R, Szilagyi P, Fiks A

Presented at the 2024 Pediatric Academic Societies Annual Meeting

Background: HPV vaccination rates remain below the Healthy People 2030 target. Quality improvement efforts can target clinicians (e.g., interventions to improve skills to address vaccine hesitancy) or practices (e.g., office procedure strategies like prompts or standing orders). Little is known, however, about the relative impact of the individual clinician contribution versus practice-level contribution on HPV vaccine missed opportunities (MOs: a visit in which a teen is eligible for the HPV vaccine but does not receive it). Identifying the degree to which clinicians or practices contribute to HPV vaccination can help target future interventions.

Objective: Compare clinician and practice-level contribution to the variation in missed HPV vaccine opportunities.

Methods: To quantify causes of observed variation in MOs, we conducted a secondary data analysis using data from 24 control practices in the practice-randomized NIH-funded STOP-HPV study with teens 11-17 years. Using data from the 12-month baseline and 6-month intervention periods, we calculated period-specific clinician-level MO rates. We then used multilevel mixed effects linear regression stratified by visit type and dose: 1) well-care (WCC) initial dose; 2) WCC subsequent dose; 3) acute/chronic initial dose; and 4) acute/chronic subsequent dose to assess practice and clinician level variation in MOs. Models included clinician-level rate of MOs (outcome), study period, # HPV vaccine eligible visits, % male teens seen, and % older (13-17) teens seen as fixed effects. Practice and clinician were nested random effects. We used the estimated variance components of the models to calculate the percentage of variability in MOs attributable to the practice and clinician, and the residual variability.

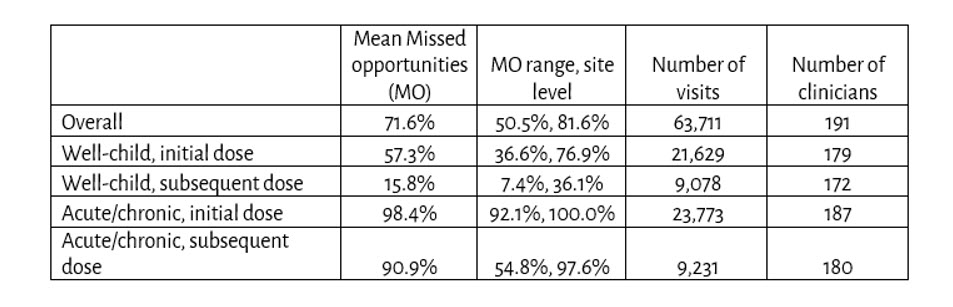

Results: Data from 191 clinicians and 63,711 visits were included in the analyses (Table). MO rates were lowest for subsequent doses at WCC visits (15.8%) and highest for initial doses at acute/chronic care visits (98.4%). Clinician and practice variability together contributed at least 35.7% of variance in MOs for all doses (Figure). At WCC visits for initial HPV vaccination, clinicians’ contribution to the variance in MOs was 36.3%; practice contribution was 21.7%.

Conclusion: Both clinicians and practices contribute substantially to the variation in HPV vaccine MO rates. While our data did not allow us to completely account for patient and geographic variation, results suggest that interventions to raise HPV vaccination rates ideally target both clinicians and practices.

Table 1. HPV Vaccine Missed Opportunities (MO) by Dose and Visit Type (24 sites)

Last Updated

05/21/2024

Source

American Academy of Pediatrics