Learning About Racism: A Star Wars Story

Nathaniel K. Jones. MD

July 29, 2019

*Editors’ note: This is one of a series of “AAP Voices” blog posts highlighting how racism impacts the health and well-being of children, adolescents, young adults and their families. To learn more, see the newly released American Academy of Pediatrics' policy statement, "The Impact of Racism on Child and Adolescent Health."

Summertime has a way of making the most mundane memories indelible. It must have something to do with the way the sun and heat make everything come alive. From the dewy moistness of sunkissed skin to the pulsating heat of summertime asphalt, to me summer never fails to make an impression. Perhaps it’s the reason I will never forget one summer in particular. For me it was the summer I learned what it meant to be black.

Now, I would be remiss to write that the advent of my racial identity is purely remembered due to simmering asphalt or sweat-soaked t-shirts. Rather it was a game of make-believe on a playground near my home that left my 7-year-old self stunned and confused.

To me and the boys around my neighborhood, Star Wars was the coolest. It was ubiquitous, from Star Wars themed birthday parties to Luke Skywalker sheets, and the idea that there was a Galaxy far far away fascinated us. Our favorite game was to act our different scenes from the movies, with each of us being a different character.

This afternoon I was with a different group of kids than I usually played with, but the game appeared to be the same. I knew I wanted to be my favorite character, Han Solo. To me, he was the epitome of the cool, charismatic tough guy I dreamed to be.

What racism feels like to a 7-year-old

The backlash was immediate. Amongst a group of largely white boys, a skinny dark skin boy just stated he wanted to be Han Solo. “You can’t be Han Solo…you’re black” hit me out of nowhere. I was confused. I mean, my skin was certainly darker than anyone in the group, but since when was that going to stop the game about space aliens? I assumed they sensed my confusion and offered me the role as Lando instead, because “…he looked more like you.”

This consolation did little to quell my confusion and what started as a promising summertime day on the playground ended up with me walking home in tears. I thought surely this couldn’t be about my skin tone, I mean we certainly didn’t have anyone who looked close to Chewbacca in our group. Were they saying I wasn’t cool or tough enough? That I couldn’t be a leader?

It was that day that mother explained racism to me. For us, the idea of race had a strange place in our household. My mother, of Asian/Pacific Islander background, adopted my sister and me at a young age. Growing up, we always got stares and looks of confusion since my mother looked nothing like my sister and me.

My mother did an amazing job balancing the reality of our racial difference while shielding us from the associated bigotry. But that day, she explained that just because we thought race didn’t matter in our family, that didn’t protect us from how much it mattered in the world around us. She opened my mind to the idea that in this world, the color of my skin would speak louder than my actions. That despite how hard I worked or how good of a person I became, the world would judge me otherwise.

“My mother did an amazing job balancing the reality of our racial difference while shielding us from the associated bigotry. But that day, she explained that just because we thought race didn’t matter in our family, that didn’t protect us from how much it mattered in the world around us.”

Racial identity: the force is strong

Now you would think the weight of the truth she shared would have crippled the spirit of a young child. But quite the opposite happened. Through that discussion, I began to be aware of the challenges that lay ahead of me, and albeit they were considerable, I wanted to work that much harder to overcome them.

The years that have followed that discussion, with the help of my mother, I began to be confident in my racial identity. In time as I grew up, it served to as a shield against the hatred and bigotry the world provided. Research cited in the new American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) policy statement, “The Impact of Racism on Child and Adolescent Health,” shows how positive racial identity in African American youths leads to positive emotional functioning and behavioral adjustment, helping to buffer the experiences of discrimination. It’s also linked with academic success, which, in turn, leads to better health outcomes as adults.

Today, it is not lost to me the protective power of positive racial and ethnic identities have for minority children. We know children of color suffer from the realities of racism every day; some as overt as a playground squabble, while most are more implicit and systemic.

However, for the longest time, the medical establishment has veered away from facing the realities of racism. In the AAP, that no longer appears to be the case. As a physician of color, I am proud to be part of an organization that sees the importance of addressing issues of racial injustice, and I use my childhood experience in this important work.

As pediatricians, we must examine the role in which we can foster positive racial identities while continuing to combat systemic inequality. We know a child’s dream will shine as bright as the world allows it. We must continue to work to allow every child’s dream to shine through, even if they just want to be Han Solo.

*The views expressed in this article are those of the author, and not necessarily those of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

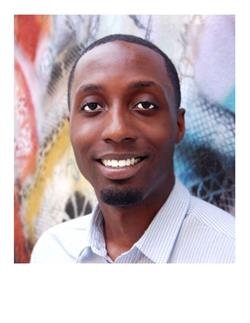

About the Author

Nathaniel K. Jones, MD

Nathaniel K. Jones, MD, a Steering Committee Member for the American Academy of Pediatrics' Provisional Section of Minority Health, Equity and Inclusion, is a Pediatric Emergency Medicine Fellow at Children’s National Medical in Washington, D.C. Follow him on Twitter at @DrNateMD