Recognizing a Different Type of Vaccine Hesitation and Centuries of Racism in Medicine

Molly Markowitz, MD, PGY3

February 4, 2021

The label “vaccine-hesitant parent” can be triggering for pediatricians. We worry about children getting and spreading serious infections, the uncomfortable conversations we must have with parents, and whether we can provide optimal care.

Stereotypically, these parents are white, well-educated, and have financial resources. They fear toxic ingredients, pharmaceutical companies, and adverse reactions. As pediatricians, we are taught to ask about, listen to, and acknowledge these fears. We then try to educate on the importance and safety of childhood vaccines.

I want to talk about a different type of vaccine-hesitant parent.

This is a parent whose fears may be rooted in hundreds of years of racism, exploitation, medical abuse, and experimentation. To be honest, if you would have asked me a year ago to identify these parents, I could not have done so. I was ignorant of how the medical system that I am a part of was founded on the experimentation and abuse of Black individuals.

“Trust is earned, and the medical community has a history of not earning the trust of Black individuals.”

As the world came to a standstill in the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic, it gave many of us the time and space to listen and reflect. As the Black Lives Matter protests again gained national media attention after the murder of George Floyd, I knew I needed to better understand how structural racism affects the patients and families I care for every day. This led me to read the critically acclaimed book “Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present” by Harriet A. Washington.

On my hour-long daily hospital commute, I listened to graphic and pervasive descriptions of how white physicians, one after another, abused and harmed Black patients to better care for white patients. With horror, I realized that not even children, often the most vulnerable among us, were exempt. These stories may have started in the past, but they continue in the present.

I would pause the book as a tightening sensation gathered in my chest. It would be enough for one day; I would listen again the next. That was my privilege; the patients in the stories, could not escape.

My view of the medical system started to shift. Every day as I walked into work, I would look up at the large banner plastered across the side of the hospital proclaiming, “Heroes work here.” I could not help but think, who are we heroes for? White patients? Black patients? All patients?

I started listening more carefully when Black parents hesitated to vaccinate their children. I began to realize that some parents’ fears may be different than my assumptions. When parents share that they don’t trust the flu vaccine because they don’t know what is in it, I no longer assume they are worried about heavy metals or preservatives. I wonder: Are they worried that we are going to cause their child unnecessary pain and suffering for the benefit of others?

Why should they trust me when I say it’s safe when it’s possible that a family member was harmed through medical experimentation or they themselves did not receive vital medical care because of the color of their skin? When we say physicians are some of the most trusted and respected individuals in our community, I now ask, by whom? White people? Black people? All people?

As the COVID-19 vaccine becomes more available to Americans, and hopefully this year to children, families will be faced with a difficult decision. This decision is about more than whether they will vaccinate their children; it is about whether they will trust the medical system with their children.

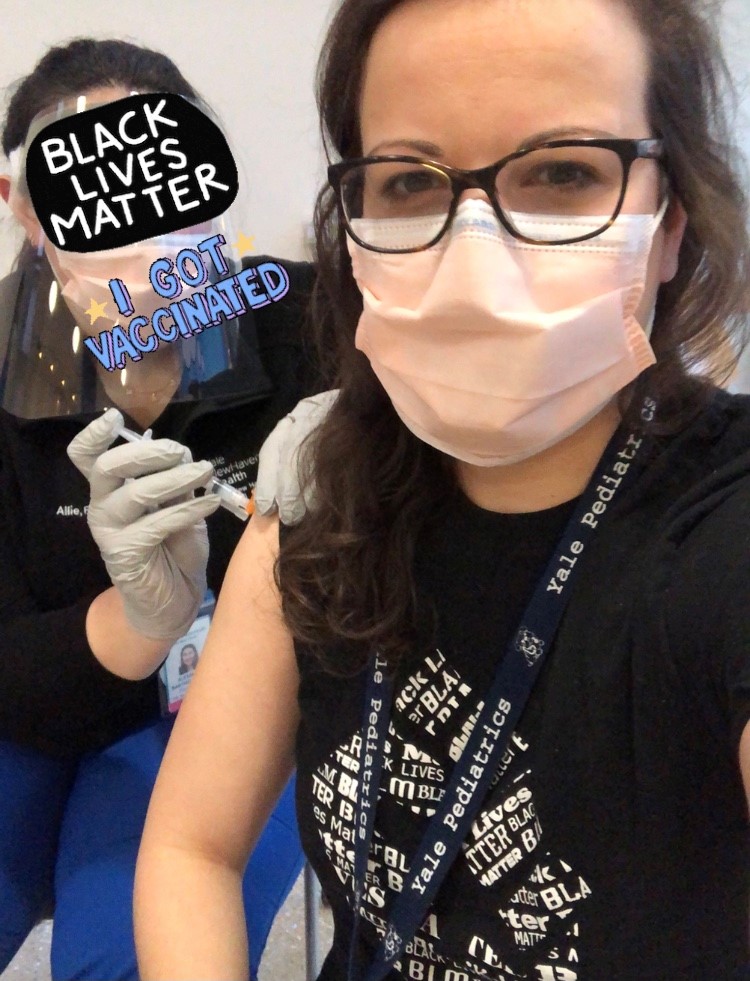

Trust is earned, and the medical community has a history of not earning the trust of Black individuals. Despite the overwhelming evidence citing the COVID-19 vaccine as safe and effective, fears will remain. I can say that I trust vaccines and know that vaccines have saved many lives and I have received both doses of the vaccine, but I recognize that may not be enough.

I’m a white pediatrician who has not experienced the years of trauma and pain inflicted on Black people, but I want families to know that I am here to listen to and to honor their fears and hesitations. I want to earn their trust. I hope to help them make the best possible decision for their family as they grapple with whether or not to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19 virus.

*The views expressed in this article are those of the author, and not necessarily those of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

About the Author

Molly Markowitz, MD, PGY3

Molly Markowitz, MD, PGY3, is a general pediatrics resident at Yale-New Haven Children's Hospital in Connecticut and editor of an advocacy newsletter for the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Section on Pediatric Trainees.