Janice L. Liebhart, MS,1 Sandra G. Hassink, MD, MS, FAAP,1 Jeanne Lindros, MPH,1 Megan R. Harrison, MPH, RD,2 Alyson B. Goodman, MD, MPH,2 Blake Sisk, PhD,3 and Stephen R. Cook, MD, MPH, FAAP1,4

1American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), Institute for Healthy Childhood Weight, Itasca, IL, U.S; 2Division

of Nutrition, Physical Activity & Obesity, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, U.S.; 3AAP Department of Research, Itasca, IL, U.S.; 4University of Rochester Medical Center, Division of General Pediatrics, Rochester, NY, U.S.

Presented at the 2018 Pediatric Academic Societies Annual Meeting.

Background: Primary care pediatricians (PCPs) play a pivotal role in responding to the ongoing childhood obesity epidemic. However, little is known about current practices on obesity treatment.

Objective: To assess PCPs’ perceptions and care related to treatment for children in 3 patient groups: overweight, obesity without complications, or obesity with complications/comorbidities.

Methods: The Periodic Survey, based on a national, random sample of AAP U.S. members, was focused on obesity in 2017 (response rate=50%). Analytic sample included practicing, non-resident pediatricians who provide health supervision (n=557). Questions covered follow-up and referrals for each patient group and perceived comfort and attitudes regarding treatment. McNemar tests compared responses across patient groups for follow-up visits and referrals.

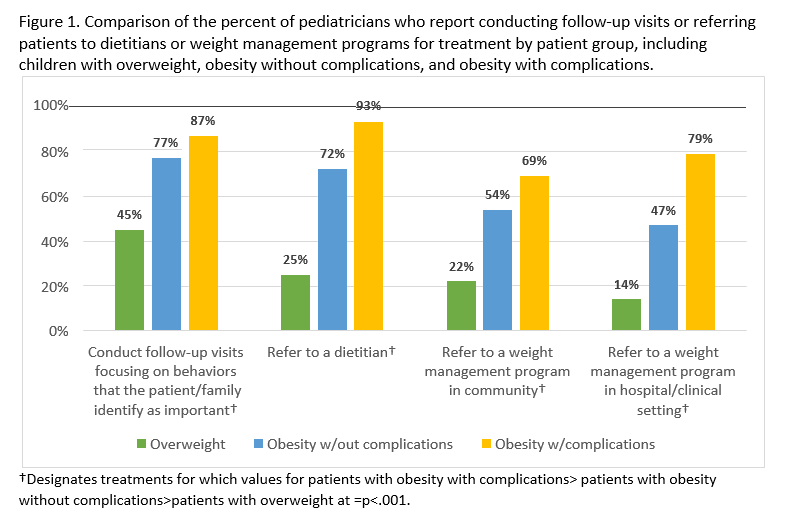

Results: For children with overweight and obesity, PCPs report being more likely to follow up and refer as the child’s BMI/comorbidities increase (Figure 1; p<.001 for all). For example, 45% conduct follow-up visits focused on behaviors identified by families for children with overweight, compared to 77% and 87% for children with obesity without and with complications, respectively. Also, for children with obesity and complications, the vast majority report not only providing follow-up visits, but also referring patients locally for treatment: 93% to a dietitian, 79% to a weight management program in a hospital setting and 69% to a community program.

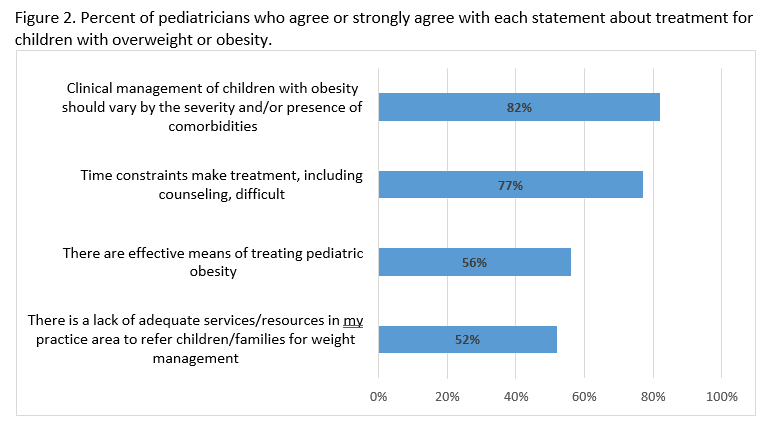

Although most PCPs report being somewhat or very comfortable monitoring behavior change goals (67%), only a modest majority (54%) report such comfort levels for behavior change techniques like motivational interviewing. Consistent with reports about practice, more than 80% believe that management should vary with severity (Figure 2). However, just 56% agree that there are effective means of treatment. Also, 77% report having insufficient time for relevant counseling, and 52% say that there are not enough resources in their area for referrals.

Conclusion: PCPs report being highly engaged in treatment for children with overweight and obesity and that their management varies with the child’s BMI/comorbidities. However, a perceived lack of time and community resources for treatment by PCPs, coupled with modest perceived levels of success and comfort with counseling suggest that both additional training and organizational/systems-level supports are needed to enhance treatment for childhood obesity.

Last Updated

10/15/2021

Source

American Academy of Pediatrics