Cull WL, Burr WH, Somberg CA, Olson LM

Presented at the 2025 Pediatric Academic Societies Annual Meeting

Background: Primary care pediatricians’ perspectives on the adequacy of the pediatric subspecialty workforce provide an important complement to other sources of workforce data such as supply counts, hospital recruitment data, and surveys of subspecialists.

Objective: To examine primary care pediatricians’ experiences with subspecialty supply and barriers to specialty care in their practice area, and to contrast the experiences of pediatricians in rural and nonrural areas.

Methods: A national sample of AAP members was surveyed through the AAP Periodic Survey in 2024 (N = 824; 41% response rate). Analyses were limited to 471 pediatricians who provide primary care. For 28 subspecialty areas, respondents were asked if there were too few, just right, or too many subspecialists to meet the needs of patients in their community. Pediatricians were also asked about potential barriers to subspecialty care for their patients. In the analyses, supply shortage was dichotomized as too few versus just right or too many, and barriers to specialty care were dichotomized as a significant or moderate barrier versus somewhat or not at all a barrier. We used independent groups t-tests to compare the responses of the primary care pediatricians from rural and non-rural areas.

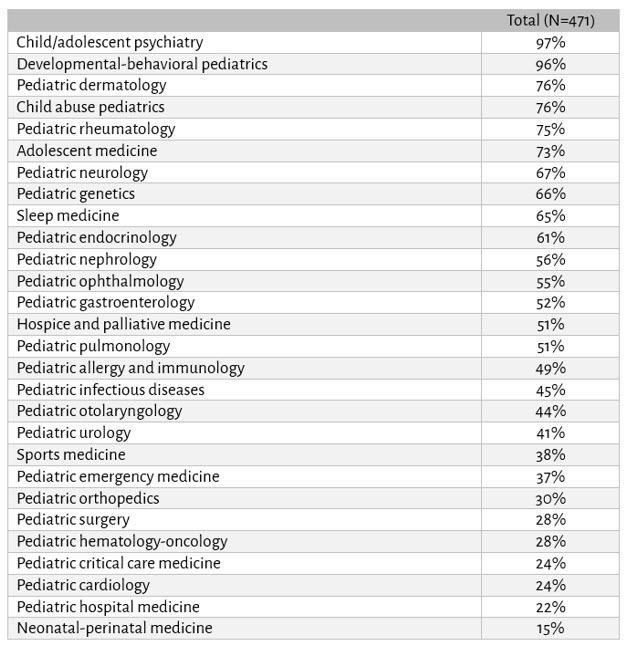

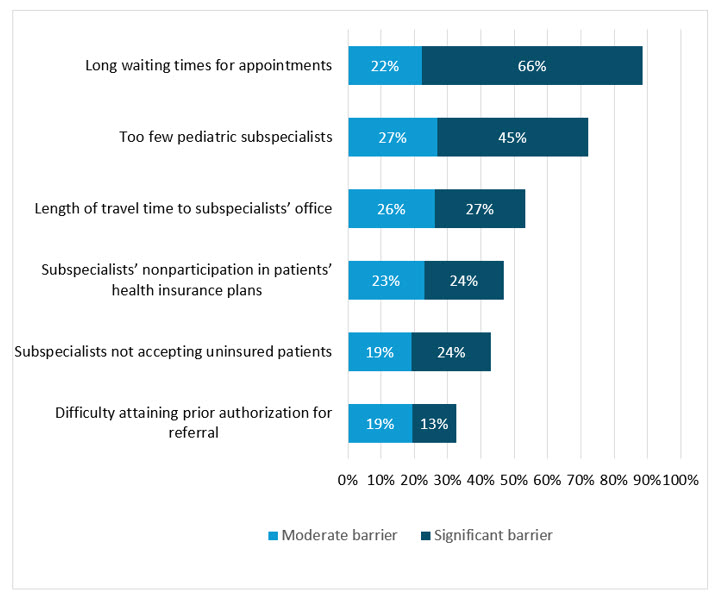

Results: Primary care pediatricians identified the following specialty areas as having the greatest shortage (% of primary care choosing too few): Child/adolescent psychiatry (97%), developmental-behavioral pediatrics (96%), pediatric dermatology (76%), child abuse pediatrics (76%), and pediatric rheumatology (75%). The greatest barriers to subspecialty care included long waiting times for appointments (88%), too few pediatric subspecialists (72%), and travel time to subspecialists (53%). Pediatricians from rural areas made up 16% of respondents, and they were significantly more likely than those from nonrural areas to report shortages for 20 of the 28 subspecialty areas (p < .o5). Rural pediatricians were also more likely than nonrural pediatricians to report travel time to subspecialists’ office was a moderate or significant barrier (86% versus 48%, p < .001).

Conclusion: Primary care pediatricians report a shortage of subspecialty care, especially in child/adolescent psychiatry and developmental-behavioral pediatrics. Shortage areas and longer travel times are more common for pediatricians practicing in rural rather than nonrural areas.

Table 1. Percentage of primary care pediatricians reporting there are too few pediatric subspecialists to meet the needs of patients in their practice community

Figure 1. Percentage of primary care pediatricians reporting a moderate or significant barriers for their patients who need pediatric subspecialty care

Last Updated

05/15/2025

Source

American Academy of Pediatrics