This article is a cross-post from Beyond the Tick Box, published March 2018

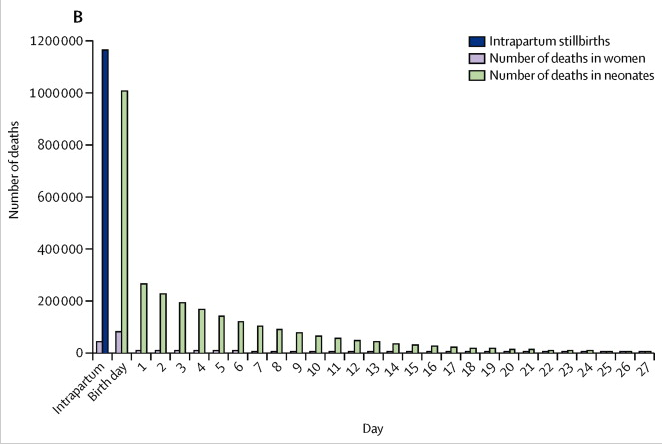

Perinatal mortality statistics make sobering reading. At the end of the Millennium Development Goals in 2015, there were an estimated annual 2.8 million neonatal deaths, of which the vast majority were on the first day of life. Notably absent from the MDGs and their new counterparts, the Sustainable Development Goals, are stillbirths. In 2015, there were still an estimated 2.6 million stillbirths, of which 1.2 million occurred after the onset of labour.

Figure 1. The number of intrapartum stillbirths, and deaths of women and babies, by day of life. Taken from Lawn et al (1)

One in ten babies require immediate help at birth. Provision of simple, safe, and effective intervention by trained birth attendants has enabled many babies to survive the most dangerous day of their lives: their birthday.

‘Helping Babies Breathe’ is the result of a collaboration between the American Academy of Pediatrics, the World Health Organization, Laerdal Global Health, USAID, and others. The initiative focusses on the use of a simple flowchart which aims to establish spontaneous breathing or ventilation support by one minute of age – within the “Golden Minute”. Implementation of Helping Babies Breathe in Tanzania has nearly halved neonatal mortality within the first 24 hours of life, and, two years later, the fresh stillbirth rate decreased by a quarter. Inspiring results! But concerning, too – the reduction in fresh stillbirth rate implies that many babies had previously been wrongly classified as dead, and had been denied resuscitation.

Shortly after completing my Neonatal Life Support training in the UK, I found myself in a remote coastal corner of Madagascar with the marine conservation NGO, Blue Ventures. I volunteered with their community health programme, Safidy, which means “choice” in Malagasy. Safidy focusses on sexual and reproductive health, water and sanitation hygiene, and maternal and child health initiatives.

Living in a small village on the coast, with very limited infrastructure, no electricity, no clean water supply, and a 200km, 7-hour trip by 4x4 on sandy rocky tracks away from the city, it is all too easy to see the challenges of delivering health care here. Serendipitously, here I met Dr Alison Leaf, a consultant neonatologist, who also saw the need for simple yet life-saving training. And so, 18 months later, we were back.

We invited all seven nurses and midwives working in the area to our ‘Helping Babies Breathe’ course. They each single-handedly ran the government health centres in their villages so whilst they were at our training, their health centres would be closed. I was in awe of my Madagascan counterparts. They managed cases on their own that we, in the UK, would manage with a multi-professional team.

The two-day course is mostly simulation, and so we spent many hours refining our acting skills and resuscitating NeoNatalie, the model baby who can breathe, demonstrate a heart rate, and cry. We had interesting and difficult discussions; for example, how to manage babies that require a higher level of care in an area where transport infrastructure is non-existent; or, where the course asks professionals to close windows and doors to reduce drafts and keep the room warm … In these health centres that would plunge the delivery room into darkness!

Testament to their enthusiasm, all participants passed both the written and practical elements of the course. None had suction or bag-valve-masks in their facilities; so we gave each nurse and midwife one of each so that they could utilise their new skills.

I returned a year later as the nurses and midwives had asked us to give training in their place of work. We trekked from health centre to health centre so that we could discuss the practicalities of actually implementing the HBB training. Midway through one training, a mum arrived with her baby: She had delivered at home with a traditional birth attendant and now the baby had an umbilical haemorrhage. The nurse treated the patient, and we resumed our training; A conspicuous example of the need to keep health centres open, and find the delicate balance between resource-intense local training, and providing more sustainable centralised training.

Over the course of my trip, we learnt that all the nurses and midwives had delivered babies, but only two had needed to use the bag-valve-mask to provide ventilation. This demonstrated that most babies do respond to simple manoeuvres. We ran a short test of theoretical knowledge and all scored well on this. However, the simulations proved a little difficult – in particular, using the bag-valve-mask correctly. We completed refresher training and subjectively, everyone seemed much more confident than they had at the end of the first training.

HBB is proven to reduce neonatal mortality and stillbirths. Bag-valve-masks and manual suction devices were specifically designed to meet the challenges of low-resource settings: they are easy to use, robust, and easily dismantled, cleaned, and put back together, ready for the next time. Anyone thinking of working in settings without formal training in neonatal resuscitation should consider becoming a HBB trainer.

Written by: Dr. Emily Clark

Edited by: Dr. Katy Smith

Further Reading

HBB is part of the wider Helping Babies Survive (HBS) initiative, which also includes training in Essential Care for Small Babies, and Essential Care for Every Baby: Visit here.

HBS complements the Helping Mothers Survive programme: Visit here.

Implementation of HBB in Tanzania: Download here.

Upcoming HBS courses: Visit here.

Other References

1. Lawn, Joy E et al. Every Newborn: progress, priorities, and potential beyond survival. The Lancet, Volume 384, Issue 9938, 189 – 205

Last Updated

11/15/2021

Source

American Academy of Pediatrics